Artwork The Oracle and the Outcast

Huge thank you's to my amazing crew: Sharon Kahanoff, Josh Olsen, Peter Hagge, Ian Barber, and Stephane Bernard for all the help.

Funding assistance provided by the Canada Council for the Arts.

At the end of the Apollo 15 lunar mission in 1971, Commander David Scott performed a live demonstration of a centuries-old theory of Galileo who proposed that objects released together (in a vacuum) fall at the same rate regardless of mass. Commander Scott simultaneously released a falcon feather and a 1.32kg geological hammer and both objects were observed to fall and land at the same time. This was expected but also reassuring, considering that the calculations ensuring a safe return journey to earth were critically based on the validity of Galileo’s early gravitational theory.

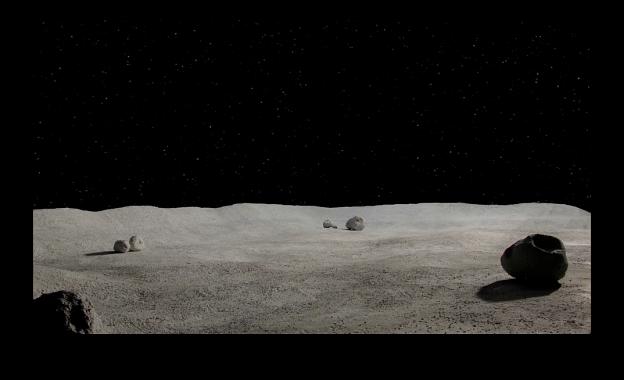

The work The Oracle and the Outcast restages the now famous lunar experiment, but proposes an on-going repetition of tests in an unspecified past/future space. Although the hammer and feather drop event remains a key moment in the film, emphasis is placed on three distinct camera identities: the god camera, the machine camera, and the body camera. These three perspectives become the central “characters” of the film, displacing the figure of the unidentified astronaut tasked with the repeated testing of the experiment.

This strategy of de-emphasizing the presence of the astronaut is important for two reasons. First, it emphasizes the environment in which he exists and where he carries out his routine task. The experiment may be routine but this isn’t to suggest it is unimportant. It is impossible to observe on earth, and so the nature of the lunar environment is critical. This landscape is also significant in that it is the only alien environment that we have yet been able to actually visit.

Second, the lack of emphasis on the astronaut means we become captivated by the experiment itself. The repetitive nature of the experiment calls into question the results of the original attempt in 1971: why repeat the task? Only when confronted by the possibility, however remote, of a different outcome does the need to repeat an experiment make sense. This points to an important aspect of science that rarely gets discussed by laypeople, namely that scientific inquiry is an on-going process. As E. Paul Zehr has recently written, science is “not absolute truth, [it] is the closest approximation to the truth we can have at any given time.” Our evolving knowledge changes with our evolving environment.

The title of the film refers to both the Greek god Apollo, also known as the Oracle of Delphi, and Galileo, the “father of modern science” who was nearly executed during the Roman Inquisition for his heliocentric beliefs and spent the rest of his life under house arrest.